NEWS CENTER

It is widely acknowledged that the development of new energy vehicles in China has been progressing at a remarkable pace, particularly for pure electric models. Bolstered by advancements in ultra-fast charging technology and battery innovation, many electric vehicle products have demonstrated exceptional performance. However, overall, the core issue affecting the public’s experience with new energy vehicles remains charging. Even when vehicles and charging points achieve perfect compatibility, most of the time it remains impossible to guarantee the same convenient refuelling efficiency for long-distance travel as petrol stations offer. This is therefore largely considered a shortcoming of all new energy vehicles.

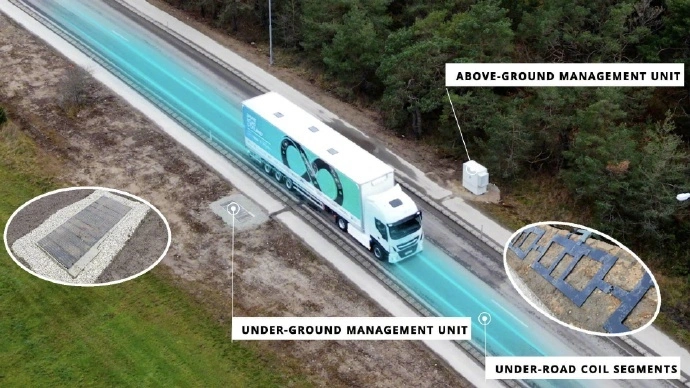

Recently, France has announced a breakthrough in automotive wireless charging technology, specifically a ‘mobile’ charging system.

Reports indicate that French engineers have installed induction coils beneath a 1.5-kilometre stretch of motorway. Vehicles equipped with bottom-mounted receivers can transfer energy to their batteries via electromagnetic induction while in motion, reportedly achieving peak power outputs of 300kW. This represents a truly formidable power figure. For context, China’s most successful wired charging system, the Li Auto 5C Supercharger, peaks at just over 500kW. Achieving 300kW during motion via wireless charging presents immense technical challenges, demanding exceptional power density from the electromagnetic induction components and unparalleled stability in near-field communication. Should the French successfully realise this, it would indeed signify a significant leapfrog in technological advancement.

According to French plans, by 2035—coinciding with the EU’s ban on fossil-fuel vehicle sales—approximately 9,000 kilometres of such electric motorways will be deployed across France. Given that the nation’s current motorway network totals less than 12,000 kilometres, this 9,000-kilometre ‘electric motorway’ network would essentially cover France’s principal trunk routes and key secondary arteries—a remarkably ambitious vision.

The technical specifications are highly ambitious, and the scale of 9,000 kilometres is truly staggering. However, the cost of such an undertaking would be astronomical. Essentially, it would involve excavating and reconstructing 9,000 kilometres of motorway. Installing the infrastructure for mobile wireless charging – including the road surface materials, charging equipment, and power supply systems – would place the project in an entirely different cost bracket compared to conventional motorway construction. Given the French penchant for romanticism and navigating bureaucratic processes, achieving even 900 kilometres by 2035 would be a considerable accomplishment, let alone the full 9,000 kilometres.

In truth, the concept of high-speed wireless charging has been in the pipeline for quite some time. Rumours circulated two or three years ago that the Hangzhou-Ningbo Expressway would support mobile wireless fast-charging technology, enabling vehicles to charge at 80% of conventional charging power while travelling at 1000 km/h. Yet, despite the passage of two to three years, this technology has yet to be implemented on this motorway.

High-speed mobile wireless fast-charging technology holds immense application potential, particularly within our domestic context where extensive motorway networks are coupled with concentrated holiday travel patterns. Driving an electric vehicle equipped with this technology onto the motorway would eliminate the need for charging stops throughout the journey. Combined with increasingly sophisticated driver assistance systems, it would be akin to travelling aboard a high-speed rail service capable of setting its own destination, hurtling along the motorway.

Naturally, from a cost and technological standpoint, the notion that the French might achieve a decisive leapfrog over our domestic new energy vehicles through high-speed mobile charging technology remains highly improbable. The rationale is straightforward: should such technology truly exist, our domestic industry would undoubtedly pursue corresponding R&D and undertake road infrastructure development. Moreover, the market aggressiveness currently demonstrated by our domestic new energy vehicles poses a far more formidable threat than the charging infrastructure itself.

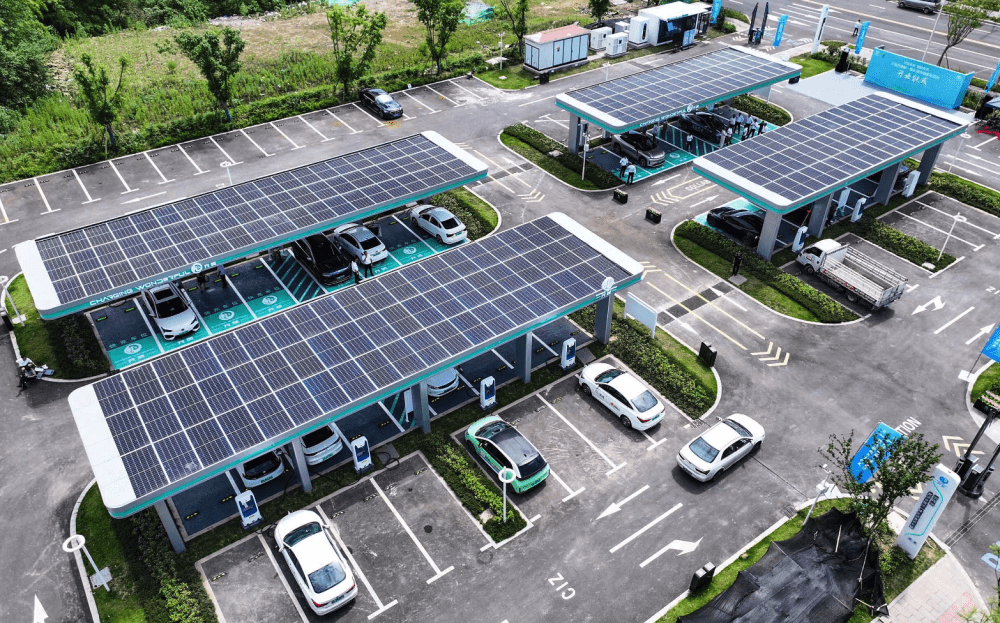

.png) PV-Storage-Charging

PV-Storage-Charging-1.png) High & Low Voltage Switchgear

High & Low Voltage Switchgear Company Profile

Company Profile News Information

News Information Service Support

Service Support Cloud Platform Customized Development

Cloud Platform Customized Development Leisheng Charging International Platform

Leisheng Charging International Platform Leisn Home Charging Platform

Leisn Home Charging Platform